"My game is like Animal Crossing and Stardew Valley!"

Like.

"This new release is Balatro but with guns!"

But with.

"It's like Fortnite meets Tetris!"

Meets.

"If you enjoy Deus Ex and System Shock, this game is for you!"

For you.

The digital commerce constantly twists its heads, the flesh of markets pulsate, and with these escapades come rapid change. New trends emerge, new tactics constantly schemed.

Today, indie marketing strategists have seemingly latched onto a new, widespread modus operandi: to take their game and explicitly compare it to more popular titles, often from which inspirations are borrowed. This nascent comparative strategy in indie game marketing serves an effort to reach larger audiences by invoking experiences familiar, and by attracting players who enjoy a similar formula. In its essence, the comparative strategy of marketing is a symbiotic handshake of convenience between players and developers. The latter even sometimes argues that comparison is a necessary strategy to survive in today's landscape. But I implore developers to stay careful on what is now an almost instinctive urge to describe your works. Comparison is but a duplicitous act—a cogent argument, a thief of joy. What you think could give your game a chance may kill any it could have ever dreamed of having.

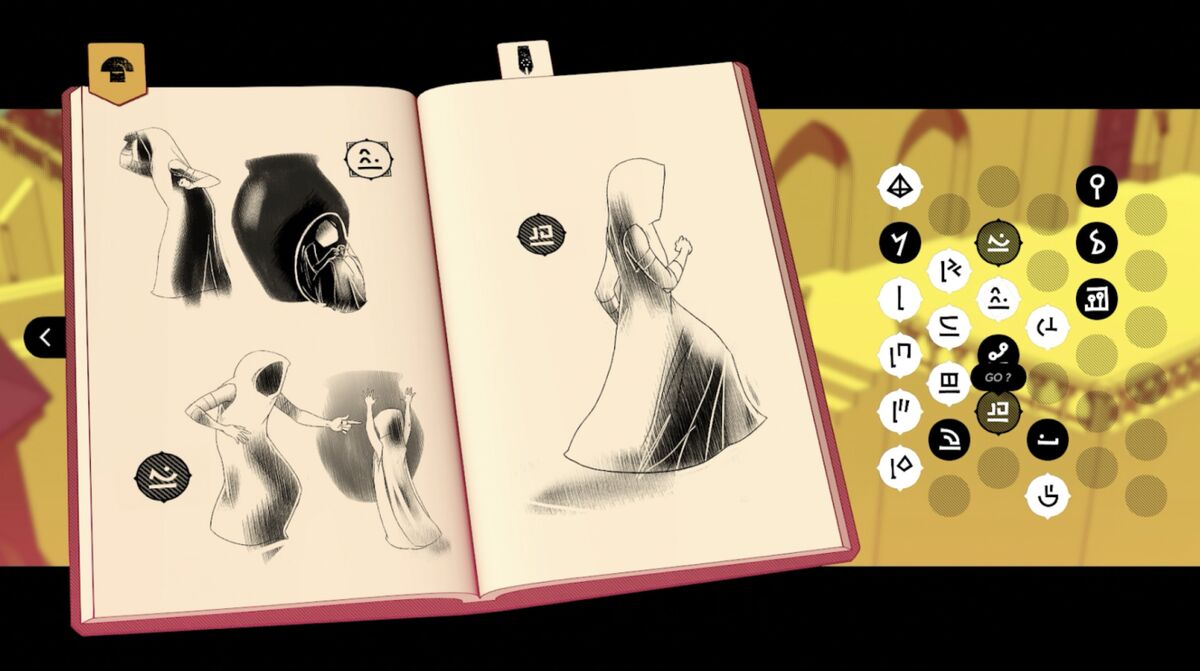

Consider supporting the game, Infinicrypt, from the post above.

It's important to differentiate the practice of comparing games in a pure descriptive sense from its related but somewhat separate practice in marketing, wherein comparison acts as a hook, of sorts, for consumers. While the former is a normal, rhetorical practice in the description of anything, it would seem that its sudden surge in usage as a hook is one of relatively modern conception. I explore the latter here, but it may well be that the two forms of comparison within the industry ricochet influence off each other.

As to why anyone would utilize a comparative marketing strategy, grabbing of attention and establishment of familiarity are the two main reasons I could see. Popularity demands focus—any title that is popular stops consumers in their scrolling, they need to see what's up. There seems to be a learned association occurring in the mind of a person whenever they see a highly popular game being compared to an indie title. In the example post for Infinicrypt above, a scrolling person may see such titles like Risk of Rain and The Binding of Isaac and proceed to feel a sense of importance—urging them to discover more about Infinicrypt. Furthermore, the strategy naturally and concisely develops familiarity among possible consumers, leading those who were already fans of the mentioned titles to feel intrigued. Fewer words are thus needed to describe and understand a game's essence; convenient references are always within reach.

Consider supporting the game, Windswept, from the post above.

Comparing games to bigger games seems to be a working strategy in driving engagement in social media, where it is most often seen. The social media account for Windswept (as shown in the photo above) echoes the sentiment: "familiarity goes a long way with hooking people in." They go on to contrast two of their posts to portray the difference in reach with and without this strategy. Without, they were able to attain 600 likes, but with it, 9,000. These results, plus the prominence of these kinds of viral marketing tactics, more-or-less displays the effectiveness of the comparative strategy in generating social media engagement.

But do they sell? If I were to see, solely, that a game is "like Donkey Kong Country", would I want to buy it from that alone?

Ultimately, what the comparative marketing strategy cannot accomplish is crucial to successful marketing: giving the product a selling point and a name. Engagement is but one metric of marketing; sold units is another. Getting engagements is arguably the easier part. However, a game noticed is not necessarily a game sold.

A product's selling point is derived from its unique existence within its competitive space. In the realm of entertainment where quality is value, the average consumer has little to no reason to purchase a product that is simply an equivalent or lower quality version of another (and, no, you must not argue that your product is somehow overall better than what you compare it with). Perhaps the most effective piece of information that would give consumers reason for purchase is some sort of uniqueness factor. In an already highly competitive market, it may be more reasonable to sell a game not on what makes it better than the rest, but what makes it different. In this manner, consumers are given reasons as to why they ought to purchase the marketed product: they are promised an experience that is new.

Comparison, however, strips uniqueness. It calls into mind other products, which gives people reason to compare, which often leads to them thinking it's a "worse" version of the other games. Through comparison, one defines oneself in the basis of others, in the language of others. Regardless of the independent quality of the product, consumers will view it through a filtered lens, seeing it not for its own merits, but for the merits of the other games referenced. Consumers may be intrigued, but if they're not hooked into buying the game (chances are they're not), they will scroll away, leaving with the impression that the game they had just witnessed is, in some effect, a collage of others, or worse, perhaps an unoriginal collage of others. Faulty associations are made; the game loses its legs. And when these faulty associations dominate the mind of the consumer, they latch, thus removing any and all unique impression the game could've possibly had.

In some more fortunate cases, indies are marketed comparatively to contrasting games, and here uniqueness could exude from the inherent "genre-mashing" (Balatro with guns?!). This lessens the problem of lacking a selling point, as the contrast of genres or tropes itself produces subversion, it is itself the selling point. But this variety of comparison still risks the game being labeled as a "rip-off" or "unoriginal", even if it is wholly unique in concept and execution. Once again, the impression made on the consumer will be defined not in the terms of the game itself, but that of others.

Consider supporting the game, Scraps of the Machine, from the post above.

It's also a matter of name. Names are identification. When we first meet somebody, we search for their name. Names guide us; they give our memories a starting point, and it is only after we remember a name do we recall its associated markers and identities. Question: what will consumers remember after scrolling past something like the tweet above? Is it the name of the comparandum or its comparans? Subject or its reference? In recollection, I surmise many consumers would remember the product loosely and in terms of the more popular games it's compared to. Worst case is consumers fail to even remember the name of the marketed game at all, probably because many of these posts fail to include the title in the first place.

https://x.com/Zingus5/status/2013353859020738654?s=20Image is from this post.

Having established the pitfalls of this strategy, let's remind ourselves of the situation's reality. Indie creators look to trends like these because the gaming industry has become hypercompetitive and overtly commercialized—as capitalist industries tend to do. It's not entirely the developers' and marketers' fault for relying on comparison to drive engagement. After all, numbers don't lie. Such trends drive (or at least promise to drive) consumer engagement, particularly from and within the crucial area of social media. However, because of the nature of social media, where everything is consumed and forgotten within seconds, engagement within it is only loosely retained, if not entirely superficial. View counts are not necessarily greater, just inflated. Comparison has its value, and it certainly pierces the algorithm, just not necessarily the people seeing the game.

There's no definitive "right way" to sell one's game, but there are ways to improve what's seen in the status quo. For instance, one thing that probably best be done is to name the game in the post. Include its title, for crying out loud. Establishing a name is establishing, too, an anchor in one's mind to associate with, to keep. Similarly, if comparison is needed, don't let it be the first thing that is attached to the game, as attention shifts too much to the comparison, burying the game's identity and selling point. Remove that unneeded filter. First impressions are long-lasting impressions.

Some of the more interesting things to result from this marketing trend are the posts exemplifying its contrary: tweets about games that take the comparison format, but twist it to focus simply on the product itself. An example would be the counter-trend of developers/marketers tweeting: "This game is for you!" as an indirect response to the comparative marketing strategy, which would normally say, "This game is for people who have played [other game]!"

Consider supporting the game, Nonu, from this post above.

Or, if this isn't enough, some go balls out and directly target the trend instead, as did the team behind UNBEATABLE, who said, "[W]e don't need the algorithm to put our games in the eyes of fans of other things."

https://x.com/dcellgames/status/199153540841643959?s=20

Marketing plays a critical role in the success of any indie game. In the hostile and competitive scene of social media marketing, where attention seems to equal profit, reaching people's feeds and grabbing their focus thus seems to be key. A trend has emerged recently, among indie creators, to compare their games to others, invoking familiarity and interest with target audiences. However, the discarding of the game's name and selling point, plus the disposability of social media posts for consumers, means that even if engagement increases through using comparison, it will not necessarily convert engagement into players. In this day and age, the consumer wants to hear new voices. Comparison on its own steals more than it gives. It may be high time for this marketing strategy to adapt, or for us to give games space to breathe and let them speak.